The Quiet Backdoor: AD Certificate Services Misconfigurations

This article is part of a series unpacking the NSA/CISA Top 10 Cybersecurity Misconfigurations through the lens of real-world breaches and assessment findings. Each entry explores how these issues manifest in live environments, how attackers exploit them, and what defenders often miss.

This entry covers Misconfiguration 1: Default Configurations of Software and Applications, with a focus on insecure defaults in Active Directory Certificate Services (ADCS).

Most teams treat Active Directory Certificate Services (ADCS) as infrastructure, not as risk. It sits quietly in the background, issuing certificates for Wi-Fi, VPN, or internal services. But when it is misconfigured, and it often is, it becomes one of the cleanest privilege escalation paths in the enterprise.

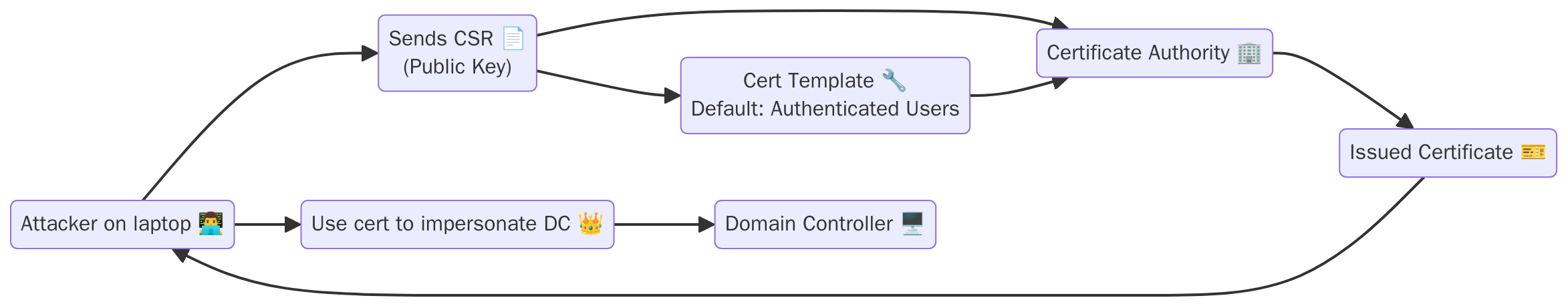

The problem is rarely visibility. It is default templates that grant excessive access. Groups like “Domain Users” or “Authenticated Users” can often request certificates that impersonate domain controllers or privileged services. Once issued, those certificates provide long-term access without triggering the kinds of alerts we typically rely on.

This article builds on the research by Will Schroeder and Lee Christensen of SpecterOps. Their Certified Pre-Owned whitepaper mapped these escalation paths in detail. In the years since, I have seen these issues persist in live environments across industries and regions .

They are not hidden. In most assessments, they show up quickly using PowerShell, PingCastle, or Certify. And yet they remain, even in environments with strong perimeter controls and EDR coverage. Certificate services are considered “done” once deployed. Nobody thinks to review them until after compromise.

TL;DR:

Misconfigured certificate templates in ADCS allow attackers to escalate privileges and maintain persistence using valid credentials. These paths rarely trigger alerts and often go unmonitored. If your templates grant enrolment to over-permissive groups, you have a backdoor.

What I’ve Seen in Practice

IIn nearly every assessment where ADCS is deployed, there is a gap. It may not be obvious at first glance, but it is there, hidden in certificate templates, access control lists, or web enrolment settings that no one has reviewed in years.

The most common issue is enrolment rights granted to broad groups. Templates often allow “Authenticated Users” or “Domain Users” to request certificates that include Subject Alternative Names (SANs), or impersonate services at a higher privilege level. These permissions are typically justified by operational needs, VPN, Wi-Fi, SCCM, or internal web services, but they now operate without scrutiny. Once deployed, they are forgotten.

Even when “Authenticated Users” is not present, over-permissive groups often are. And in most environments, there is no alerting on group membership changes. The logging may exist, but the signals are lost in the noise. A user requesting a certificate from a trusted template looks legitimate. Until you realise that certificate grants domain-level access, bypasses MFA, and never touches a password.

The ADCS web enrolment portal is another persistent soft spot. It is almost always enabled, reachable over HTTP, and accessible to all standard users. The internal-only justification is common. So is the lack of segmentation. Once an attacker is inside the network, that portal becomes a low-effort entry point to persistence and escalation. Templates like UserAuthCert, ComputerTemplate, WirelessUser, and WebServer sound benign. But when they include client authentication EKUs and are open to wide groups, they become silent privilege escalators. And they rarely show up in detection pipelines.

These misconfigurations are not buried. Tools like PowerShell, PingCastle, Certify, and PSPKIAudit surface them quickly. But because ADCS is seen as infrastructure rather than a security boundary, the risks are deprioritised. If you want to fix this, do not start with detection. Start with control. Restrict template enrolment permissions to tightly scoped groups. Monitor those groups for changes. Review every template that allows client auth or smart card logon. And disable web enrolment entirely unless you have a very good reason not to.

Final Thoughts

ADCS was designed to make authentication easier. In many environments, it does that a little too well.

Misconfigured templates give attackers a way to mint trusted credentials without ever cracking a password or triggering a lockout. The access looks legitimate because, technically, it is. That’s what makes it so effective, and so often overlooked.

The fix is not complex. It just requires ownership. Someone needs to be responsible for reviewing template permissions, limiting web enrolment exposure, and treating ADCS like the privilege boundary it is. Because from an attacker’s perspective, these misconfigurations are not infrastructure quirks. They are access paths. If it can issue trust, it needs to be trusted. And that trust should be earned, not assumed.

Get in touch