PAM is Not Enough: When Forgotten Accounts Bypass Your Controls

This article is part of a series unpacking the NSA/CISA Top 10 Cybersecurity Misconfigurations through the lens of real-world breaches and assessment findings.

This entry continues Misconfiguration 2: Inadequate Identity and Access Management, with a focus on privilege sprawl in Active Directory environments. It examines how nested groups, unmanaged service accounts, and unmonitored changes to privileged roles quietly undermine identity tooling like CyberArk, Delinea, and Azure PIM. What starts as administrative convenience often becomes a silent breach path.

TL;DR

PAM is only as strong as what it sees. Nested groups, unmanaged service accounts, forgotten appliance credentials, and silent AD modifications all provide privilege escalation paths that routinely bypass detection. If your controls stop at Domain Admins or naming convention based groups like CyberArk Admins VMWare, you are not tracking the real threat surface.

Privilege creep is rarely malicious at the start. It happens in layers. A group inside a group. A local account left behind. A service account the vendor promised to rotate but never did. What starts as operational convenience becomes a breach enabler when visibility fades and alerts never fire.

In multiple real world assessments, I have seen this play out across global and hybrid environments. A privileged group like Workstation Admins might appear clean at the top level, only five users, well understood. But one nested group down sits another, and another, until suddenly you find 50 users with admin rights nobody was tracking. Teams assume their controls are comprehensive. But attackers know the difference between visible privilege and effective privilege.

This article examines how forgotten accounts, unmonitored group changes, and neglected SaaS or appliance credentials quietly erode the promise of privileged access management. It is not just a tooling gap. It is an architecture and ownership problem. And one attackers are more than happy to map.

Assigned but Unwatched: When Privilege Becomes Permanent

Privileged identity and access management platforms like CyberArk and Delinea are meant to reduce standing privilege and limit access to those who need it, when they need it. But in practice, I often find environments where these systems provide the illusion of control rather than the reality.

One of the first things I look at during an assessment is how many users are assigned to privileged roles and how long those assignments have remained unchanged. It is not uncommon to find domain groups like CyberArk Admins VMWare or Delinea SA Storage containing dozens of members who have been there for months or even years. The group may have been created during a migration, vendor project, or support ticket, and never properly cleaned up. There may be no expiry date, no justification record, and no active owner. The group persists, but nobody is quite sure why.

This is especially dangerous when the naming conventions are predictable. If an attacker compromises a standard user account and sees a list of group memberships with consistent naming, they know exactly where to look. Most teams have alerts tied to Domain Admins or Enterprise Admins. Very few extend that same scrutiny to the nested or role-specific groups that actually grant privileged access in day-to-day operations. If your alerting only covers the top-level AD groups, the attacker has room to manoeuvre.

I have seen attackers add themselves to privileged groups tied to password vaults or session managers without detection. If Active Directory permissions are not locked down, and if no alerts are tied to changes in those lower-tier groups, the attacker inherits access to your vault, your jump hosts, and your infrastructure. The vault becomes the attack surface.

Cloud environments are not exempt. Azure Privileged Identity Management is designed to offer just-in-time elevation, but in the wild, the model often breaks down. In many organisations, roles like Global Administrator or Privileged Role Administrator are marked as eligible but never reviewed. I have seen environments where eligibility was granted years ago and never re-evaluated. In some cases, the roles in question were not even standard. Custom Azure roles with broad tenant permissions were still active, and not included in any alerting or review cycle.

Because these custom roles fall outside the default reporting scope, they go unnoticed until something breaks. By then, it is too late. One organisation I assessed had a custom role with global read and write permissions across all Azure subscriptions. It had no expiry, no approval workflow, and no record of who created it. The access was permanent in everything but name.

Whether you are using CyberArk, Delinea, or Azure PIM, the story is the same. Privilege assigned without enforcement becomes standing access. Standing access without monitoring becomes a breach path. If your privileged identity and access management tooling is not backed by visibility, expiry, and real ownership, then it is not a control. It is just a record. And one the attacker is counting on.

The Hidden Chain: Nested Groups and Privilege Creep by Design

Most organisations assume that their privileged groups are tightly controlled. When asked, the IT or security team will confidently say, “Only five people have Workstation Admin rights,” or “We review Domain Admins monthly.” But in practice, those numbers are rarely accurate. I have used PingCastle during assessments to map group hierarchies, and what starts as a small, visible set of users often unravels into dozens or even hundreds of accounts—granted indirect but effective privilege through nested group structures nobody thought to check.

This is not just a tooling oversight. It is a false sense of certainty. Even when organisations use controls like Local Administrator Password Solution (LAPS), the assumption is that membership in administrative groups is already well understood. But LAPS does not fix what it cannot see. If a privileged group contains another group, and that group contains yet another, the net effect is elevated access granted far beyond what the organisation believes.

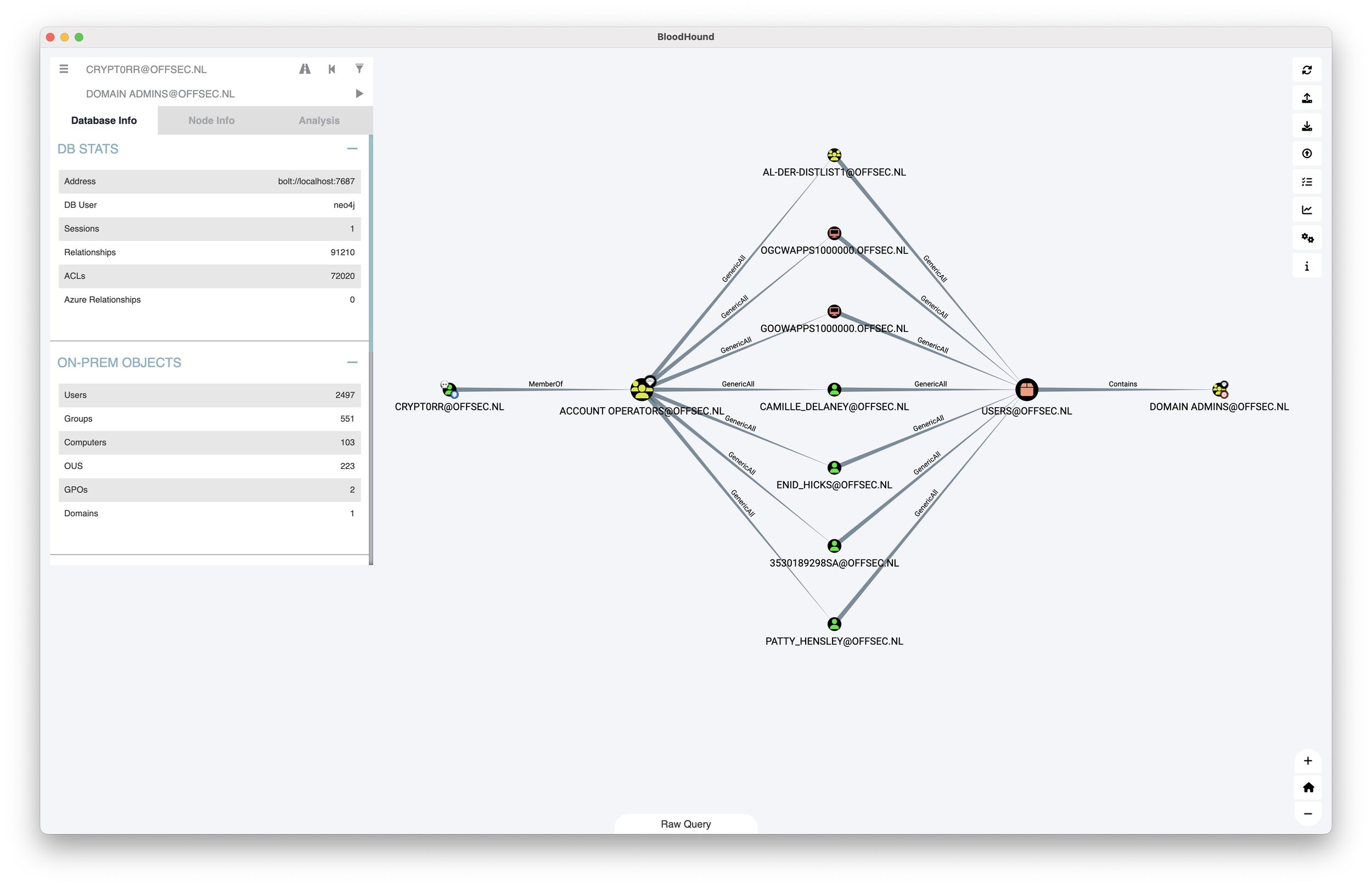

Attackers know this. Tools like BloodHound make it trivial to map privilege escalation paths in Active Directory. Once a foothold is established, all it takes is one overlooked group membership, one legacy OU with excessive delegation, or one admin tier where visibility was assumed but never confirmed. Legacy Active Directory environments are particularly susceptible. The older the environment, the more likely that mergers, acquisitions, and administrative shortcuts have introduced complexity nobody owns. I have seen production domains linked to UAT or test environments through long-forgotten trust relationships that still grant meaningful access.

And then there is the naming problem. Most privileged groups are plainly labelled. Others use basic naming obfuscation—project codes, abbreviations, or themes like animals or geography—but they still have to be human-readable. If the group makes sense to the admin, it eventually makes sense to the attacker. I once saw an environment using fish names for sensitive groups. It did not take long to figure out which ones were sharks.

Even in organisations that have invested in privileged identity tooling, the same blind spot appears. Group structures are visible through tools like Active Directory Users and Computers, but that visibility stops at one level deep unless you intentionally trace the chain. If you rely on the default GUI view, or never run recursive queries, you are missing the structure the attacker will exploit.

The underlying problem is not technical. It is procedural. Most teams do not treat nested group sprawl as a security issue. They see it as an administrative convenience. But privilege by inheritance is still privilege. If the group has access to a jump host, a file share, or a vault, then so does every user it contains, no matter how far down the chain they sit.

Outside the Vault: The Accounts Nobody Owns

For every identity brought under control by privileged identity tooling, there is another left out entirely. These are the accounts that exist outside the vault, beyond the PIM workflow, and often without clear ownership. They are still privileged. But they are nobody’s responsibility until something goes wrong.

Service accounts are a common example. In many environments, application owners resist onboarding these accounts into privileged identity platforms. The reason is almost always operational risk. They will say, “If we rotate this password, the application will break,” or, “This service was built ten years ago and cannot handle a strong password.” Sometimes the password uses special characters that trigger encoding issues. Other times, nobody wants to touch it because the original implementers are long gone. Out of sight becomes out of scope.

These legacy accounts are especially dangerous because they tend to live in cleartext configuration files, scripts, or unsecured registry entries. They are rarely monitored. They often have interactive logon rights when they should not. And they are almost never rotated. From an attacker’s perspective, this is a dream. Static credentials with elevated rights that nobody is watching.

Then there are the edge appliances. Firewalls, storage arrays, load balancers, and out-of-band management tools like iLO or iDRAC all ship with local administrator accounts. These are sometimes vaulted at the management plane, but often left in place with their default password or a shared credential used by vendors or internal teams. I have seen organisations that vaulted access to Panorama but left the individual Palo Alto firewalls unmanaged. Same with VMware. Same with NetApp. If the assumption is that a central controller makes the individual devices safe, the attacker will simply go around it.

SaaS platforms are another weak point. While Microsoft environments are typically better integrated into identity workflows, third-party platforms often fall outside the governance boundary. Tools like Salesforce, Confluence, and Jenkins commonly have local administrator accounts that are not tied to SSO. These accounts are often intended for break-glass use, but rarely tested. In some cases, they were never even documented. They just exist, waiting to be discovered.

The most dangerous omission I have seen in recent years is Okta. Organisations that move aggressively to federate access across hundreds of internal apps will sometimes forget to create a break-glass account for Okta itself. If Okta is compromised, or simply unavailable, they are locked out of everything. I have seen organisations remember to create break-glass accounts for Azure or their PIM system, but forget to do the same for the identity provider they have placed at the centre of everything. And once an attacker controls Okta, they control the login flow for every other platform.

These accounts do not sit in AD. They do not trigger group change alerts. They do not show up in your standard identity reviews. But they exist. And because they exist outside structured controls, they become the weakest link in your privilege chain.

Closing the Gap: Seeing What the Attacker Sees

The biggest challenge in privileged identity security is not a lack of tools. It is a lack of alignment between what defenders assume is controlled and what attackers can actually reach. To close that gap, visibility must extend beyond Domain Admins, beyond CyberArk or Azure PIM dashboards, and into the messier parts of the environment that no one wants to own.

Start with enumeration. During assessments, I often use tools like PingCastle to map out nested group structures and delegation chains. Even ADExplorer will work. The output can be confronting. Groups that were thought to contain five users might balloon to fifty or more once nested relationships are resolved. I recommend clients run these tools themselves—both because it builds internal capability, and because it should not take an external consultant to show you what your own directory looks like.

From there, make privilege changes observable. Whether the account is tied to an on-premise domain, a cloud provider, an appliance, or a SaaS platform, the moment it gains administrative rights, someone should know. If it is not used often, alert the moment it is used. If it is used regularly, ensure there is a workflow to justify why. Changes to identity provider sync groups, break-glass logins, and shared service accounts should never be silent. They should light up the dashboard.

Most teams get this right for traditional infrastructure. But they often miss business critical applications that do not feel like infrastructure. In law firms, platforms like NetDocuments, iManage, or Relativity may hold sensitive case data, yet lack administrative logging or approval workflows. In engineering firms, proprietary modelling tools or workflow systems may carry privileged access to internal data or intellectual property. If it appears on your business impact assessment, it should be subject to the same privilege discipline as your domain controllers.

Enforcement cadence is up to each organisation. Quarterly reviews may work in some cases. Change advisory board reviews may be overkill in others. What matters more than the cadence is the principle: if an account can access the control plane—whether it is domain, cloud, appliance, or SaaS, it should be visible, justified, and treated as high risk. And that visibility should be owned by someone.

When you cannot win the process argument, refocus the conversation. Do not blame the application owner. Do not argue about who is responsible. Just show them what the attacker would do. Highlight the static credentials sitting in startup scripts. Show the group sprawl in BloodHound. Show the privilege path mapped in PingCastle. Most people are not trying to be negligent. They just do not realise how thin the line is between architectural drift and breach.

The Tooling Mentioned:

Below are recommended links to embed or reference for transparency and further reading:

PingCastle: https://www.pingcastle.com/download/

BloodHound (by SpecterOps): https://github.com/BloodHoundAD/BloodHound

LAPS (Local Administrator Password Solution): https://learn.microsoft.com/en-us/windows-server/identity/laps/laps-overview

Microsoft Azure PIM: https://learn.microsoft.com/en-us/azure/active-directory/privileged-identity-management/pim-configure

CyberArk Privileged Access Manager: https://www.cyberark.com/products/privileged-access-manager/

Delinea Secret Server: https://delinea.com/products/secret-server

Get in touch